The Broken Window Theory introduced by James Q. Wilson and George L. Kelling in 1982 describes the escalating negative impact of low-level neglect or crime such as broken windows or even littering can have on a society.

In fact, if a single broken window in a neighbourhood or suburb is not repaired quickly it is very likely that other windows will be vandalised soon after. Following the first broken window not only will further windows follow but people will also break into the effected properties continuing the cycle of vandalism and property damage. It becomes only a question of time before a neighbourhood sicks into chaos and disrepair.

Many years before the publication of the broken window theory, Philip Zimbardo a psychologist from Stanford, California concluded a parallel theory using two vehicles he purposely abandoned in two contrasting neighbourhoods. One was abandoned in Palo Alto, California and the other in the Bronx, New York. Within only a few hours the car abandoned in the Bronx was broken into. First the car stereo was stolen then its windows smashed until the completely vandalised vehicle was simply used by children on the street as a form entertainment. All in the space of only 24 hours.

The second car in Palo Alto, California on the other hand was not vandalised for an entire week until Philip Zimbardo began to vandalise it himself by concisely breaking its windows. As he expected very quickly others in the neighbourhood followed this pattern of negative behaviour.

He concluded that even littering the streets, to some perhaps a minor neglect of ones surroundings and society, can start a cycle of very negative behaviour.

Another example, a smoker is more likely to simply dispose their finished cigarette by throwing it into the streets if they see others are doing this also. Thereby feeling less personally responsible for his cigarette dirtying the streets.

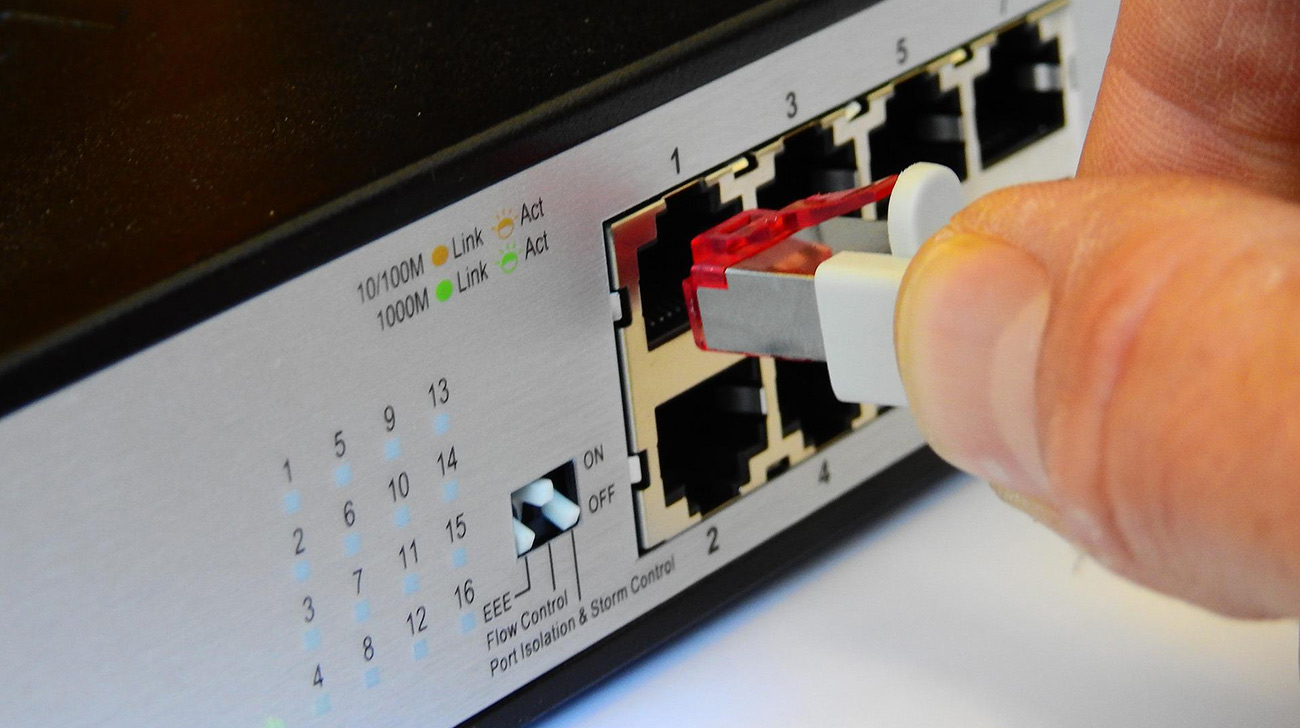

Having structured network cabinets is exactly the same – technicians are more likely to follow suit and pay attention to detail using cable management solutions as intended.

However despite best intentions sooner or later due to deadlines and pressures technicians find it increasingly difficult to maintain an organised structure.

For example senior management having an important online meeting when the network connection drops. The technician will no-doubt receive a very emotional and stressful phone call to “fix” it. Always eager to ensure the connection is live again as soon as possible patching cables in a tidy fashion is understandably their lowest priority. Often promising themselves to revisit the site at a later date to tidy up the chaos created. Despite best intentions in reality this is often impossible or too costly.

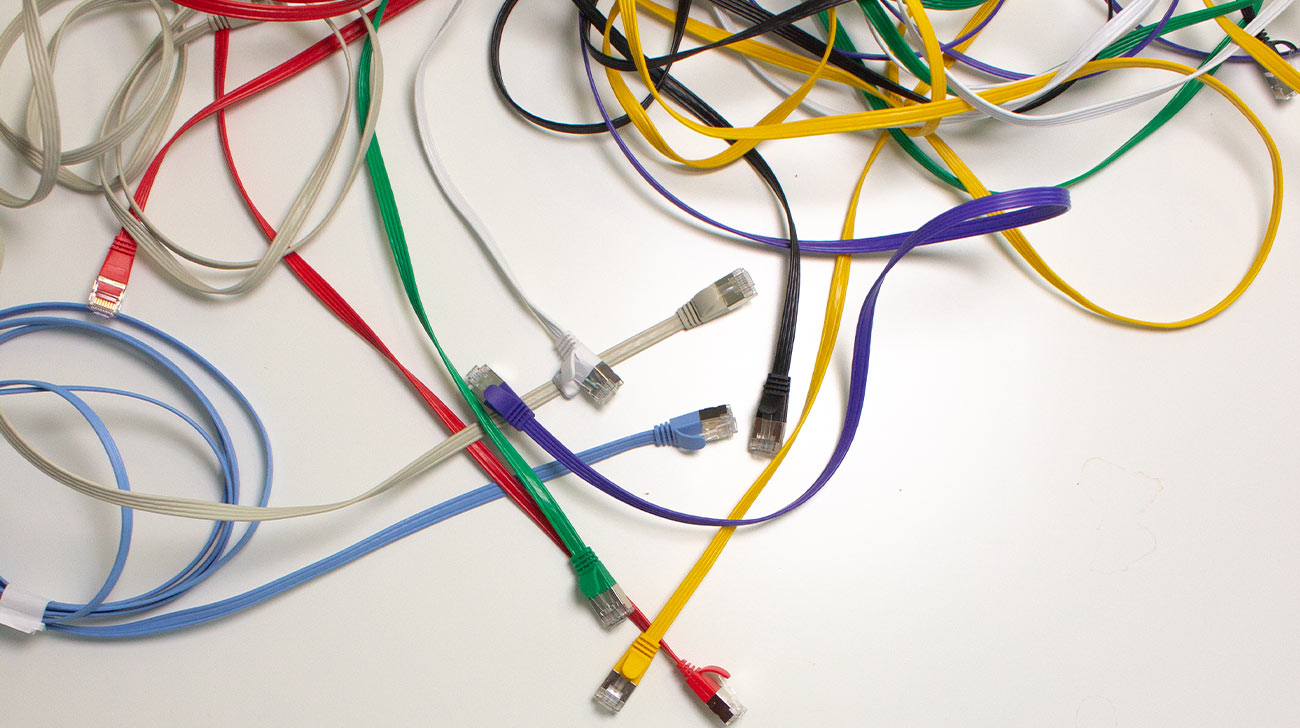

This is the broken window theory in the IT workplace. The chances of chaotic patching increases rapidly with every patch that is not installed in the correct way. In no time at all one ends up with cable spaghetti making it impossible to replace or install new equipment without completely removing all patch cables and re-patching from the cabinet from scratch.

Therefore the most important challenge is to keep network cabinets organised. Otherwise one must spend excessive time and money cleaning up the mess that others have unintentionally made. There is of course another way, in patching utopia, where you don’t ever have to worry about cable length or cable spaghetti.

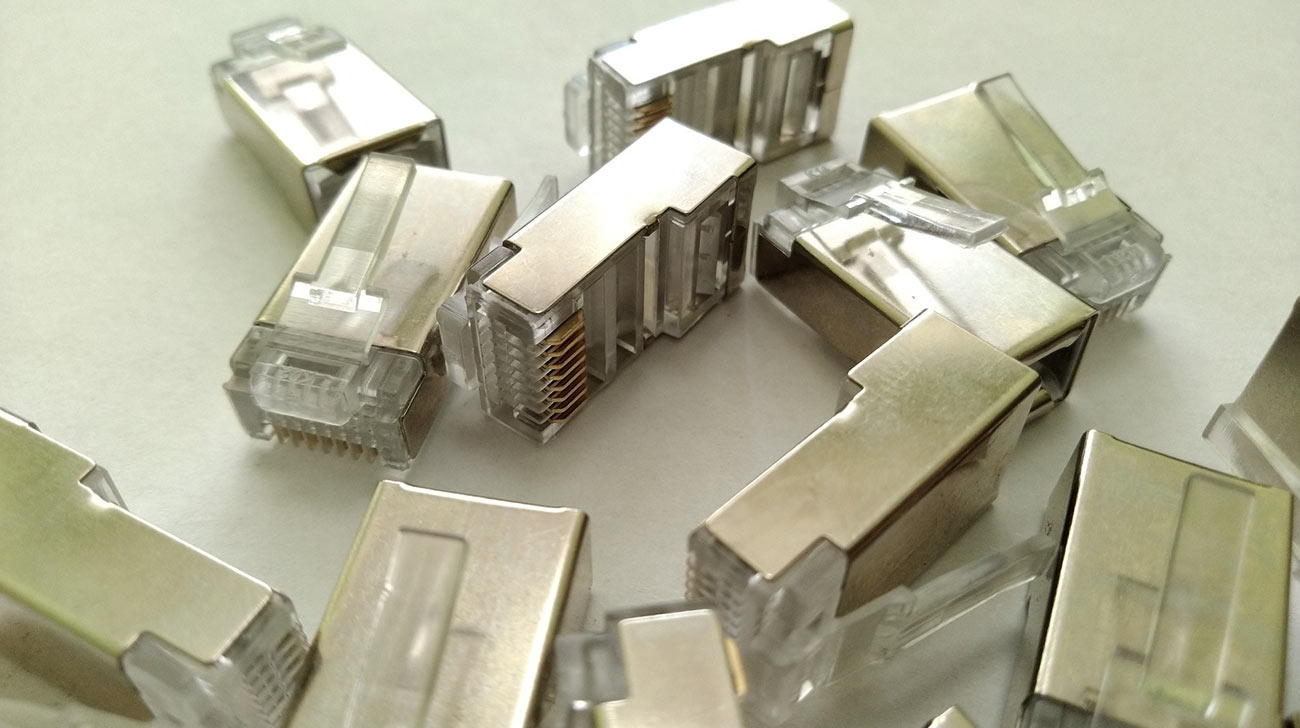

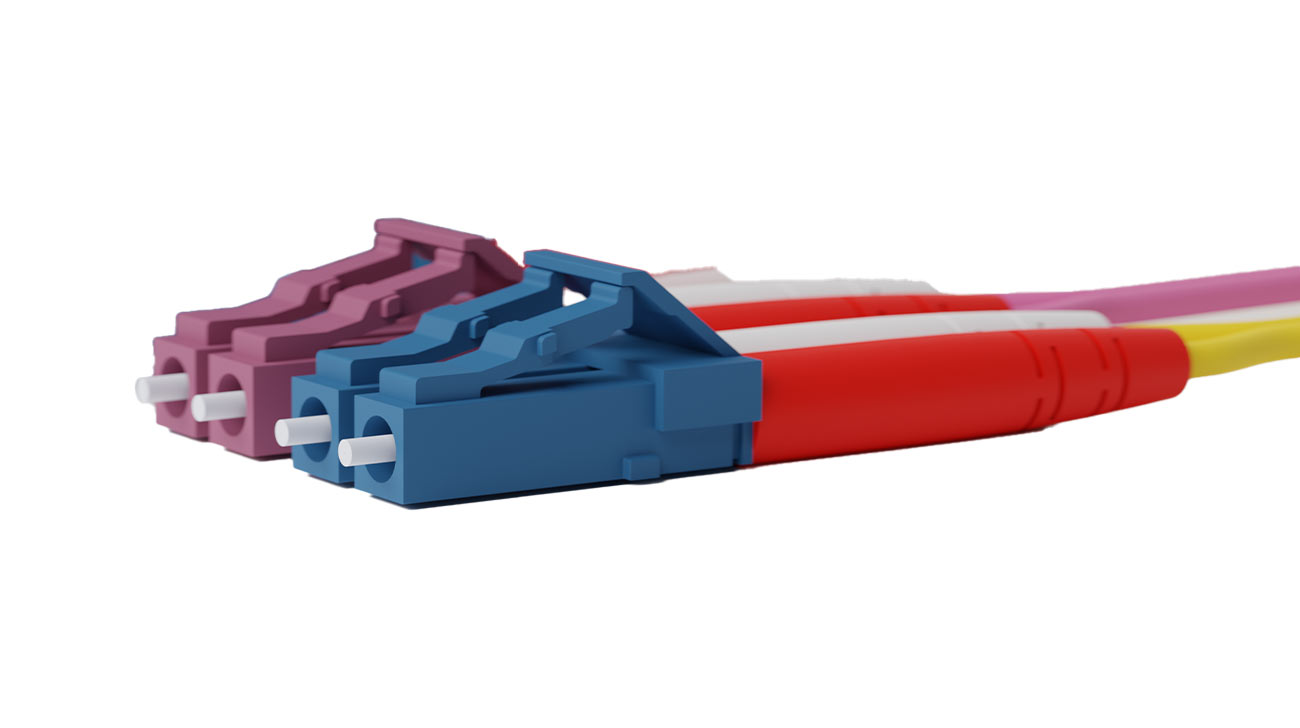

The solution; PATCHBOX – each cable being exactly the right length when required and self-contained securely when not required.